On a humid Accra morning, a veteran newspaper vendor named Kwame Nyame sits by his once-bustling newsstand near Kwame Nkrumah Circle, staring at unsold piles of Daily Graphic and Ghanaian Times. “I used to sell 300 copies a day; now selling 50 is a challenge,” he laments. His story is echoed by print vendors across …

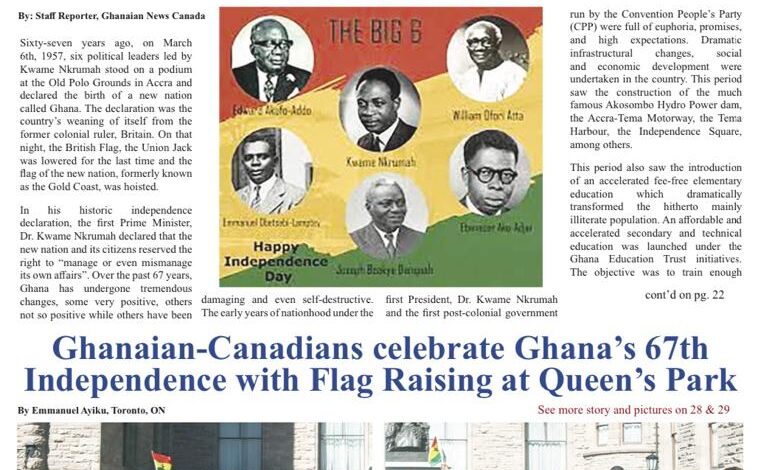

Will Traditional Newspapers Survive the Digital Era in Ghana?

On a humid Accra morning, a veteran newspaper vendor named Kwame Nyame sits by his once-bustling newsstand near Kwame Nkrumah Circle, staring at unsold piles of Daily Graphic and Ghanaian Times. “I used to sell 300 copies a day; now selling 50 is a challenge,” he laments. His story is echoed by print vendors across Ghana: the digital revolution is battering traditional newspapers, raising a pressing question – can they survive in the era of smartphones, social media, and instant news? This issue is sparking debate in media circles, from newsroom boardrooms in Accra to Parliament’s communications committee. Some see an inevitable decline; others argue newspapers can adapt and carve a new role. In this op-ed-style analysis, we evaluate the state of Ghana’s legacy newspapers, the headwinds they face, and the strategies that might keep them alive (or not) in a rapidly changing media ecosystem.

The Print Decline: By the Numbers

There’s no sugar-coating it: Ghana’s newspapers are experiencing a sharp decline in circulation and readership. The signs are everywhere. Publishers have hiked cover prices as print costs rise (Ghanaian Times now costs GH₵10 per issue), and those price increases further depress sales. Vendors report that many longtime customers have simply stopped buying papers, because “all the newspaper content ends up on social media early in the day”. Radio and TV morning shows routinely review the newspaper headlines, effectively giving people the gist for free, by 7am. Why spend ₵10 on a paper when you heard the main news on Peace FM’s “Kokrokoo” or saw it on Twitter?

Statistics back up the anecdotal decline. While exact national circulation figures are closely held, a research paper notes a “sharp decline in circulation and readership of printed newspapers in favor of internet news” in Ghana’s urban areas. The number of print newspapers on the market has dwindled as well – Ghana once had dozens of active titles; now “the number of newspapers… has been reduced to a little over 40” in recent years. Many smaller papers and regional weeklies have folded due to low sales. Even the big dailies print far fewer copies than a decade ago.

One vivid metric: vendors like Nyame are selling one-sixth the copies they used to (300 down to 50). Another longtime seller, William Odame, who started in 1989, says frequent cover price hikes (Daily Guide at GH₵8, Chronicle GH₵8, etc.) have driven away many buyers. Those who still buy tend to be older loyalists or institutions that need a physical paper for records. The average Ghanaian’s news habits have shifted decisively online. Afrobarometer surveys show that by 2017, 87% of Ghanaians said they “never or rarely” read a newspaper. That’s nearly nine in ten people essentially not touching print. Meanwhile, 48% were getting news from social media at least a few times a week – a trend that’s only accelerated since.

For advertisers, these numbers ring alarm bells. Dwindling circulation directly undermines newspapers’ value as an ad medium. Fewer readers mean fewer eyeballs for ads. Many organizations – from private companies to government ministries – have quietly slashed their print ad budgets or canceled bulk subscriptions. “Many organizations have cut down on their annual newspaper subscriptions,” notes Azure Abdulai, reflecting on Ghana’s print advertising landscape. In the past, banks or telecoms might have bought hundreds of copies of papers daily for branches and clients; now they rely on digital newsletters or online news. The correlation is straightforward: as print circulation drops, ad revenue drops in tandem, threatening the business model of newspapers.

Adapt or Perish: How Are Newspapers Responding?

Facing these grim trends, Ghana’s newspapers are scrambling to adapt. One major strategy has been pivoting to digital platforms – essentially becoming online news outlets in addition to print. Today, almost all major Ghanaian newspapers have an online presence and publish content on the web. Graphic Communications Group (publisher of Daily Graphic, Graphic Showbiz, etc.) runs Graphic Online, a news website that is updated throughout the day. Ghanaian Times has its content on the Times website and shares news via social media. Private papers like Daily Guide and The Chronicle similarly have websites or partner with news portals like ModernGhana or GhanaWeb to push their stories. In fact, about 80% of newspaper publishers in Ghana have integrated web operations with their print editions. This is a survival move – if readers won’t buy the paper, at least capture them online and try to monetize via ads or maintain relevance.

Some have gone further to offer digital subscriptions or e-papers. The state-owned Daily Graphic launched the Graphic NewsPlus app, a digital replica of its newspapers that readers can subscribe to for a fee. For example, one can pay GH₵12.50 for a week’s access to all Graphic publications on the app. This gives die-hard readers (especially those abroad or who prefer reading on a tablet) a way to read the full newspaper electronically. While it’s a promising concept, it remains a niche service – the vast majority of online readers stick to the free news on Graphic’s website rather than paying for the PDF-like e-paper. Daily Guide briefly experimented with a paywall for exclusive stories but saw limited uptake. The culture of paying for online news is not yet ingrained in Ghana, so newspapers walk a tightrope: charge and lose audience, or give content free and struggle to monetize it.

Another adaptation has been diversifying content and language. Legacy papers recognize they can’t compete with the internet on breaking news – Twitter will beat them every time. But they can offer in-depth analysis, investigative reporting, or specialized stories that readers might not find elsewhere. Daily Graphic has tried to position itself as the paper of record, providing comprehensive coverage of national events and more detailed reports (e.g., full texts of the budget speech, investigative pieces on social issues) which can complement the quick online headlines. Some papers have introduced dedicated weekly pull-outs or magazines within the paper focusing on areas like education, lifestyle, or agribusiness – niches that still have committed audiences and advertisers.

Language and local reach are another front. Ghana’s print media historically has been English-dominated (aside from a few local language papers which have mostly died out). But to attract more readers, especially younger ones who may be more comfortable reading in local languages or pidgin, newspapers could integrate bilingual content or columns in Akan, Ewe, Ga, etc. We haven’t seen major moves there yet – likely because literacy in local languages in print is still limited – but there’s potential. The state broadcaster GBC, for instance, prides itself on broadcasting in 27 Ghanaian languages now, up from 6 previously. Newspapers might not go that far, but perhaps offering translations of key articles online could widen their appeal (for example, a Twi summary of a big political story on the website).

We must note, however, that simply having a website is not a panacea. Online advertising in Ghana generates only a fraction of the revenue that print used to bring in. Digital ads (banners, sponsored content) suffer from lower rates and widespread ad-blocking or user indifference. As a result, newspapers’ digital ventures have struggled to replace lost print income. Many newspaper websites are actually run on shoestring budgets, often just reposting the day’s print articles. They compete with native digital news sites (like Pulse Ghana, GhanaWeb, Citinewsroom.com) that often have better SEO or faster updates. In essence, Ghana’s newspapers went online, but so did everyone else – the competition there is arguably fiercer and more crowded than the print newsstand ever was.

The Edge Newspapers Still Have

Yet, it’s not game over for print quite yet. Traditional newspapers retain a few advantages and roles that digital-only media haven’t fully replicated.

One is credibility and depth. There’s still a perception among some segments that if it’s in Daily Graphic, it’s authoritative. Newspapers have long-standing reputations and experienced journalists who provide context to stories. Advertisers note that newspapers offer a level of gravitas – certain types of content, like legal notices, public announcements, obituaries, etc., are still better suited for print. Indeed, newspapers continue to earn revenue from these statutory and classified ads that must be printed by law or tradition. For example, government procurement notices and court summons are often required to be published in print – a niche but steady source of income. As Azure Abdulai points out, “Statutory publications… still find a fitting home in newspapers”. It’s hard to imagine a family paying for a Facebook ad to announce a loved one’s funeral – they’d rather see it in the newspaper’s obituary section for posterity and respect. This gives newspapers a lifeline of content and ads that won’t immediately vanish.

Another edge is certain demographics. While youth have migrated online, older generations and some rural audiences still prefer print (or at least trust it more). Advertisers targeting, say, senior professionals or long-time subscribers may continue with newspaper ads because that segment isn’t on TikTok or Instagram. Also, many libraries, offices, and schools keep physical newspapers for reference – these institutional subscriptions keep some print runs going. “For certain demographics, particularly older generations not as engaged with digital media, newspapers remain a trusted source,” notes Abdulai. Though this audience is shrinking, it’s not negligible yet.

Newspapers also offer a curated, comprehensive package of news that websites can’t exactly match. The experience of reading a print paper – scanning headlines, finding stories you might not actively search for – has its own value. Some media analysts argue that the newspaper format encourages a more informed citizenry by bundling diverse topics (politics, business, sports, etc.) in one issue, whereas online readers might silo themselves into niches. In Ghana, where misinformation spreads rapidly on social media, the curated and edited content of newspapers can act as a corrective, ensuring people get verified information. (Of course, newspapers are not immune to misinformation or bias, but the editorial standards tend to be clearer.)

That said, the open secret is that all newspapers now also chase online audiences, so even their credibility advantage is tied to digital presence. Many stories that break in the newspaper end up circulating as screenshots on WhatsApp by midday. In a sense, the print edition has almost become a byproduct – a physical confirmation of what’s online, rather than the primary source.

The Hard Truths: Challenges to Survival

Despite adaptation efforts, the challenges threatening newspapers’ survival are immense. Economic sustainability is problem number one. Running a newspaper – paying journalists, printing, distribution – is costly. With falling sales and ads, many papers operate at a loss or rely on parent organizations for subsidy. The state-owned papers (Graphic, Times) have government backing (though they are expected to be commercially viable, they have a cushion). Private papers often have political patronage or side businesses (some publishers also own printing presses, leveraging that). But in pure market terms, it’s tough to justify daily print runs when the ROI is negative. Some experts predict we may see frequency reductions – e.g., dailies becoming weeklies – to cut costs. A few Ghanaian magazines have done this or gone fully digital.

Another challenge is the changing consumer behavior that’s hard to reverse. Young people who never picked up a newspaper in their teens are unlikely to start in their 30s. The habit of the morning paper is dying with the generations that practiced it. In urban areas, the morning routine has shifted to checking WhatsApp, Twitter, and news apps. Even older folks are learning to use smartphones for news (often added to family WhatsApp groups that share daily news summaries, replacing the need to buy a paper). This generational shift means the trajectory for print is largely one-directional.

Moreover, the competition from digital media is relentless. Not only do newspapers compete with digital-born outlets for audience, they also compete for advertisers with Google and Facebook, which offer targeted ads and vast reach. Many Ghanaian SMEs that might have put a small ad in the local paper now just boost a Facebook post for a fraction of the cost. This siphons off the lower end of advertising that newspapers used to count on (classifieds, small display ads). It’s a classic disruption story: the cheap, efficient new technology (online ads) erodes the base of the old (print ads).

Politically, newspapers in Ghana have played a watchdog role and shaped discourse, but now that agenda-setting power is shifting to radio, TV, and online media. Politicians still engage with newspapers – issuing rejoinders, granting interviews – but they increasingly bypass them by posting statements on Facebook/Twitter or speaking directly on radio/TV talk shows. During elections, one still sees campaign ads in newspapers, but far more money is poured into radio jingles, billboards, and social media campaigns targeting youth (the so-called “TikTok electorate”, as one article dubbed new young voters). The fear is that if newspapers lose relevance in influencing public opinion, they could lose a raison d’être beyond just recording history.

Possible Futures: Reinvention or Extinction?

So, will traditional newspapers survive? There are a few possible paths forward:

- Reinvention as Digital News Brands: In this scenario, newspapers accept that the physical print product may eventually cease, but the institution survives by fully transforming into a digital news outlet. Daily Graphic, for example, might one day stop the presses but continue as Graphic Online, with the same journalistic standards and identity. This would mean focusing on web, mobile apps, video content, podcasts, etc. Essentially, the legacy brand leverages its reputation to compete online. We’re already seeing steps in this direction, but monetization (via paywalls or ads) must be solved for it to be sustainable. Some global papers (like the New York Times) have done this successfully with digital subscriptions – perhaps Graphic could too, if they offer unique enough content. The challenge: Ghana’s market is smaller and less willing to pay for news, so it might require downsizing operations to match modest digital revenues.

- Niche and Premium Print: Newspapers could pivot to being less about breaking news and more about analysis, features, and weekend reads – essentially like a news magazine. Printing fewer issues (say, a thick weekend edition) might maintain a loyal readership who enjoy the leisurely, in-depth content. The daily ephemeral news would all go online, while the print product becomes a premium offering (with high-quality paper, maybe bilingual content, special reports, etc.). Perhaps people would pay for a well-curated weekly that they wouldn’t for a thin daily repeating what they saw on Twitter. This approach banks on the idea that print becomes a prestige or specialty product, not a commodity. There’s a hint of this already: the weekend editions of papers often sell slightly better than weekdays because they have extras like magazines or sports pull-outs.

- Integration with Broadcast: We might see newspapers more tightly integrate with radio/TV, effectively becoming content providers for broadcast and then compiling that content in print. For example, a newspaper could partner with a radio station to have its journalists discuss their stories on air (some do) and use the radio platform to drive interest in detailed articles. Alternatively, a media house might merge its print and broadcast newsrooms to produce content that is repackaged across print, web, and radio. This convergence can cut costs and cross-pollinate audiences. Ghana’s media groups are thinking this way: Multimedia Group has radio, TV, online – if they owned a newspaper, they’d likely unify reporting staff. The downside for newspapers is that in such a merge, the print edition might eventually be deemed unnecessary when content is already reaching people via faster channels.

- Unfortunately, one must consider Extinction: It is possible that many traditional newspapers will simply not survive as businesses. They could run out of funds, lose all advertisers, and fold. Some might pivot to become solely online and drop the print edition (as a few magazines have). Others might be kept on life support for political reasons – for instance, a partisan paper might be funded by a party benefactor despite losses, just to have a propaganda outlet. But those aren’t thriving in true sense. We could, in a decade, have only one or two major national newspapers still printing daily (perhaps Daily Graphic and maybe one private daily), with the rest fully digital or defunct. It’s noteworthy that globally many newspapers have closed or gone digital-only; Ghana wouldn’t be an outlier if that happens.

From an optimistic standpoint, newspapers could survive by transforming. They have certain strengths: brand legacy, archives of content, trained journalists, and trust that upstart blogs may lack. If they capitalize on these – for instance, by offering fact-checked, responsible journalism as an antidote to the chaos of online rumors – they can retain a critical role. Some readers might come back to quality over quantity. “We still need journalists who dig for the truth,” you might hear an editor argue, “and our newspaper provides that in-depth truth amidst the fake news online.” Indeed, in an era of misinformation, a trusted newspaper (print or digital) is valuable.

The government and society can also influence survival. If the Ghanaian government decided to, it could support print media through policies – perhaps tax breaks on newsprint, or requiring more public notices in papers. However, any overt support runs the risk of undermining editorial independence or being seen as propping up a dinosaur. Interestingly, vendor Nyame in Accra even appealed, “The government must step in to support us”. While a direct bailout is unlikely, there is recognition that a collapse of newspapers could hurt public accountability. Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee recently fretted over GBC’s language services, showing officials do care about media access. If newspaper decline is framed as a threat to informed democracy, perhaps there’ll be more urgency in finding solutions.

Nevertheless, the market reality is that survival will depend on innovation and resilience. Some Ghanaian newspaper publishers are demonstrating resilience – cutting costs, leveraging their content on multiple platforms, and engaging readers on social media. For example, Daily Graphic runs active Twitter and Facebook pages and even does video explainers now, essentially stepping out of the print-only mindset. They’re fighting to stay relevant in the daily conversation.

To answer the question bluntly: Will traditional newspapers survive? In their current form, likely not all of them. Some will perish, some will endure by evolving. The form of a “newspaper” might change from newsprint to an app or newsletter (as Jamlab suggested, perhaps converting papers into email newsletters to retain readership and revenue). Content is king, and the newspaper organizations that focus on content quality while embracing new delivery formats stand the best chance. Those that cling stubbornly to old ways – ignoring the digital writing on the wall – may join the archives of history.

In Ghana’s media narrative, we may very well witness a dramatic transition but not a complete extinction. The romance of holding a physical paper may become a niche nostalgia, but the journalism and storytelling at the heart of newspapers can find new life in the digital era. Perhaps one day we’ll refer to Daily Graphic not as a “newspaper” but as a “news organization” and think nothing of it. As a wise editor once remarked, “We’re not in the newspaper business, we’re in the news business.” The quicker Ghana’s papers internalize that, the better their odds of survival in whatever form the future demands.

Subscribe to MDBrief

Clean insights, a bit of sarcasm, and zero boring headlines.