As we scroll, share, and like, Ghanaian media professionals face an urgent ethical question: How do we uphold journalistic integrity when fake news runs rampant online?

The Ethics of Social Media Journalism in Ghana: Battling Fake News

In Ghana today, a rumor on WhatsApp can spread faster than harmattan fire, and a tweet from an “influencer” can feel as authoritative as a GBC newscast. Social media has undeniably democratized information – everyone with a phone can be a “journalist” now – but it’s also turned the media landscape into a high-stakes battleground for truth. As we scroll, share, and like, Ghanaian media professionals face an urgent ethical question: How do we uphold journalistic integrity when fake news runs rampant online?

When Misinformation Goes Viral

Not long ago, a false report of a former president’s death rippled across Facebook and WhatsApp, causing national alarm until it was debunked. We’ve seen COVID-19 conspiracies take root on social media, from claims that the virus “targets only whites” in Ghana to miracle cure hoaxes. During elections, doctored images and AI-generated audio clips pop up, attempting to tarnish candidates – for example, a network of bot accounts on Twitter (X) in late 2024 pushed hashtags like #1TouchForBawumia with coordinated misinformation, even using AI-generated profile photos to appear legit. The age of “deepfakes” and digital deception is here, and Ghana is not immune to its effects.

The consequences of unchecked fake news are dire. It can skew election discourse, as incendiary false claims amplify ethnic and political tensions. It erodes trust in legitimate news – if people keep getting hoodwinked by fake stories, they start doubting all stories. According to an Afrobarometer survey, 86% of Ghanaians believe social media makes people more likely to believe fake news, and only 39% say they trust information on social media at least “somewhat”. Yet, paradoxically, millions rely on these platforms daily for news updates. It’s a classic case of the fox guarding the henhouse – social media is both the source of misinformation and the space where it must be corrected.

Journalists vs. the Wild West of News

For bona fide journalists, social media is a double-edged sword. On one hand, it’s an indispensable tool for gathering news tips, reaching audiences, and building personal brands. On the other, it’s a minefield of unverified info, partisan spin, and clickbait – and stepping wrongly can blow up one’s credibility. The ethical mandate for Ghanaian journalists now extends beyond the traditional “verify your sources” to “verify that viral tweet before retweeting,” and “don’t amplify an unconfirmed WhatsApp video just because it’s trending.”

Unfortunately, the pressure to be first with the news can tempt even seasoned media houses to grab tidbits off social media without full verification. Recall the embarrassing episode when Ghana’s state broadcaster GBC aired news of former South African President Thabo Mbeki’s “death” – sourcing it from a satirical website post making the rounds, without realizing it was fake. If GBC can slip, no newsroom is invulnerable. The lesson: the old-school rules of fact-checking are more crucial than ever in the social media age. A journalist’s reputation may hang on that one retweet of a false rumor – and by extension, their outlet’s reputation too.

Ghana’s media community is responding by beefing up fact-checking training. The Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA), for instance, has been actively training journalists on fact-checking techniques ahead of the 2024 elections. Many newsrooms now have policies: e.g., two credible confirmations before publishing any user-generated content, monitoring known fake-news peddlers to avoid their traps, etc. There’s also a growing practice of issuing quick corrections on social channels when something false slips through – transparency that is essential to maintain public trust.

The Influencer Factor: Part of the Problem or Solution?

In Ghana, influencers – be they bloggers, YouTubers, radio hosts with big Twitter followings, or even celebrities – often serve as de facto news sources for their followers. This is a huge responsibility, though not all treat it as such. We’ve seen instances of popular figures sharing misleading information: perhaps a musician tweeting an out-of-context political video with an inflammatory caption, or a social media personality forwarding a dubious health “tip” (salt solution to prevent COVID, anyone?). In chasing clout and engagement, some influencers inadvertently (or sometimes intentionally) become superspreaders of fake news.

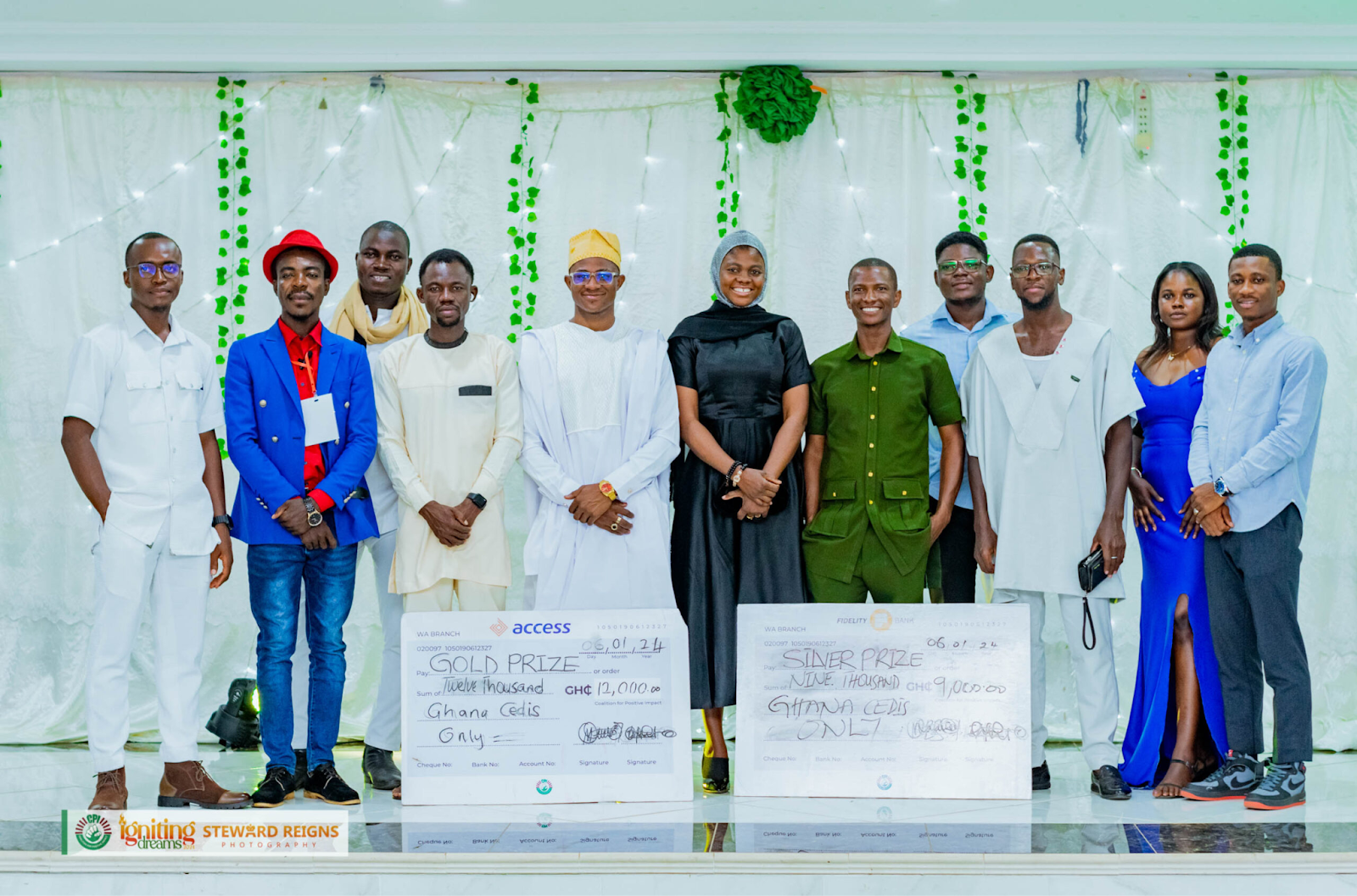

But influencers can also be powerful allies in the fight against misinformation. Recognizing this, fact-check organizations in Ghana have started to collaborate with influencers. Ahead of the 2024 polls, Fact-Check Ghana (an initiative of MFWA) actually trained social media influencers to help debunk false narratives in local languages. The reasoning: these online personalities speak the language (literally and figuratively) of the digitally savvy public, and if they are equipped to call out fake news, their fans will listen. It’s a smart strategy – imagine your favorite comedian on Instagram posting, “Guys, that viral voice note about election rigging is fake. Here’s the proof.” That carries a different weight than a dry rebuttal from an official source.

Some Ghanaian influencers have embraced this role. Take for example influential bloggers who now partner with fact-checkers to run “fake news alert” segments on their platforms. Or radio presenters who pause their shows to clarify that a trending story is unverified. These are positive developments. The hope is to create a culture where spreading truth is just as trendy as breaking news, and where clout is gained not by being outrageous, but by being reliable.

Institutional Efforts and Ethical Lines

On the institutional side, several players are stepping up. Fact-Check Ghana (established 2016) is now a well-known resource, debunking everything from political lies to social media hoaxes in real time. There’s also Dubawa and Africa Check collaborating in Ghana to bolster fact-checking. During the 2020 elections and gearing up for 2024, these groups formed a coalition and situation room to monitor and respond to mis/disinformation crises. Essentially, they’ve created an emergency response system for fake news – something akin to a fire service for information fires. This is a commendable move that paid dividends: for eight days around the election, the coalition tracked rumors, identified fake news “hotspots,” and addressed them before they could spread further.

However, one must note: while fact-checkers can douse many false flames, the source of the fire – the ease of publishing lies with zero accountability – remains. That’s where some call for stronger regulation. Indeed, Afrobarometer data shows 77% of Ghanaians think the government should limit or prohibit the sharing of false news. But this is a slippery slope. We’ve seen elsewhere how “fake news laws” get abused by authorities to silence dissent or critical journalism under the guise of fighting misinformation. Ghana, thankfully, has no sweeping fake news law at the moment, and our courts and media advocates would likely push back against any overly broad censorship. The onus thus falls on self-regulation and education rather than government policing truth (which rarely ends well for democracy).

So, what are ethical lines Ghanaian journalists should draw? Firstly, separate opinion from fact – on social media, reporters often share personal opinions, but they must clarify it’s opinion, not a news report. Second, no sharing unverified info, even with a disclaimer – saying “Source: social media” isn’t an excuse; if you can’t vouch for it, don’t amplify it. Third, engage in corrections: if a media house mistakenly spreads a false piece (it happens), they should correct it with the same energy and reach as the original post. This is about maintaining trust. And finally, educate the public: news organizations here have started doing media literacy segments (“How to spot fake news” tips on air and online). The more people can critically assess what they see online, the less they’ll be fooled – relieving pressure on journalists to play refuter all day.

A Balancing Act for the Future

The fight against fake news in Ghana is ultimately a fight for the soul of our information space. We pride ourselves as one of Africa’s vibrant democracies with a relatively free press. But that freedom can be exploited by bad actors (foreign or domestic) who find fertile ground on Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, and WhatsApp. Journalists and ethical influencers are the front-line defenders in this new war. They must battle not only the fakers, but sometimes their own instincts to chase virality.

Encouragingly, Ghanaian media is adapting. The 2024 elections will be a major test – already, efforts are in place to ensure rumors don’t set the agenda. It will require collaboration: tech companies need to tighten content moderation, media must coordinate on debunking narratives (perhaps a shared database of known false stories), and citizens should be empowered to question and verify before believing sensational claims.

In our Ghanaian parlance, we like to say “Drums don’t beat in a vacuum.” If fake news is the loud drumbeat on social media, then let the truth be the kpalongo dancer that outshines it. Through ethical journalism and collective vigilance, we can ensure that facts ultimately drown out falsehoods. It’s not easy – the misinformation peddlers are cunning (some even using AI to fabricate content that looks real). But as the saying goes, “No lie can live forever.” With perseverance, our media can expose lies for what they are, and reinforce that cherished Ghanaian value: integrity.Let’s all remember that a free society relies on truthful information. If we allow fakery to flourish, we undermine our own freedom. The next time you’re about to share that unverified “breaking news” post, pause and think: am I helping inform, or mislead? It’s a question not just for journalists, but for all of us who participate in the new media ecosystem. In this fight, everyone with a phone is effectively a journalist – and thus, everyone has a bit of responsibility. Together, we can snuff out fake news, small small.

Subscribe to MDBrief

Clean insights, a bit of sarcasm, and zero boring headlines.