Ghana’s tech ecosystem has long pinned hopes on homegrown brands to break the country’s reliance on imports. In the early 2000s RLG Communications emerged as the poster child of this vision: founded in 2001 by entrepreneur Roland Agambire as a small mobile-phone repair shop, it quickly expanded into assembling laptops, desktops and handsets locally. RLG …

Made in Ghana: Tech Innovators RLG and Zepto in Retrospect

Ghana’s tech ecosystem has long pinned hopes on homegrown brands to break the country’s reliance on imports. In the early 2000s RLG Communications emerged as the poster child of this vision: founded in 2001 by entrepreneur Roland Agambire as a small mobile-phone repair shop, it quickly expanded into assembling laptops, desktops and handsets locally. RLG even launched branded “sales & service” kiosks and institutes across Ghana, and the government lauded its “Made in Ghana” products.

The company won awards, many of them. In 2012 it was ranked the second–best Ghanaian company by the Investment Promotion Centre, and secured headline collaborations notably with Microsoft to supply Windows-equipped laptops in 2012.

Zepto Limited, which is often misspelled “Zeptor”, arrived a decade later with similar ambitions. In 2010 it relocated a Danish electronics assembly plant to Accra, claiming to have built “the first technology production plant in Ghana”. Zepto marketed itself as Ghana’s local manufacturer of flat-screen TVs and laptops, aligning with national projects like the TV digital-migration.

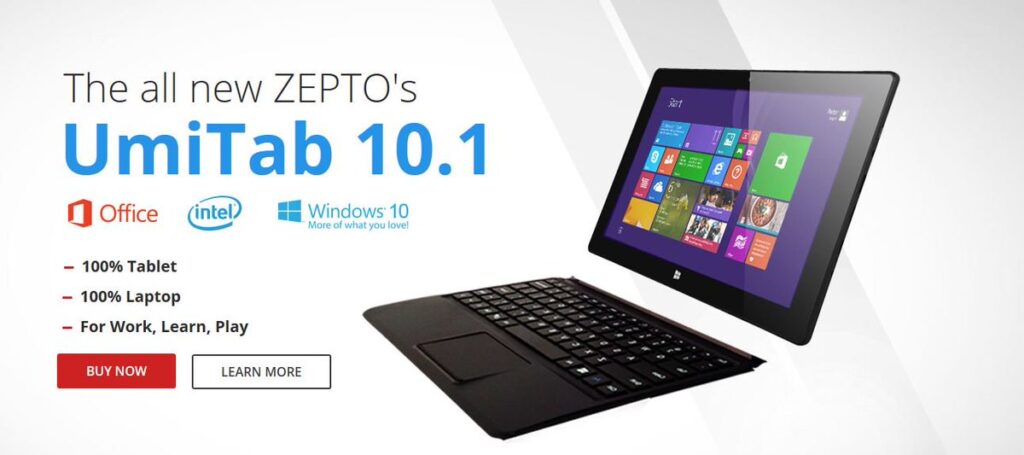

By 2012 it was supplying hundreds of laptops to Ghanaian teachers and, in partnership with Microsoft, launching an affordable Windows tablet (the “UmiTab”) in 2016. These two companies RLG and Zepto served as a beacon of Ghana’s tech aspirations. But a critical look reveals contrasting outcomes and important lessons.

RLG Communications: A Pioneering ICT Enterprise

RLG Communications was once celebrated as Ghana’s homegrown ICT champion, with branded kiosks and training centers nationwide. Founded in March 2001 by Roland Agambire, RLG began as a modest mobile-phone repair outlet and rapidly grew into an indigenous tech manufacturer and trainer. It claimed to be the first African firm to assemble laptops, desktops and phones locally, and focused on training Ghanaian youth in computer and phone repairs. In its heyday RLG won recognitions for innovation and entrepreneurship. Roland, its CEO was even named Marketing Man of the Year in 2011, helping to solidify public confidence that Ghana could build its own tech industry.

By the early 2010s RLG had diversified its products and partnerships. It launched its own mobile-phone lines (the G-Series, later “Viva” and “Fusion” Android models) across West Africa.

A 2012 deal with Microsoft meant RLG laptops shipped with genuine Windows 8 software. RLG also entered into ambitious joint ventures. In 2015 it announced Hope City, a $10 billion tech park near Accra to be built with government support, and it won high-profile government contracts to promote ICT locally. Ghana’s Ministry of Environment, Science & Technology awarded RLG a ¢51.3 million contract in 2010 to supply 103,181 “Better Ghana” laptops to schools. It later secured another deal to assemble 60,000 digital TV set-top boxes for the national digital-TV migration. RLG even expanded abroad, opening offices in Dubai, Nigeria, China and other African countries. Expectations were sky-high: RLG was framed as a vehicle for job creation, promising thousands of tech-sector jobs, and technological self-reliance.

Yet, from the mid-2010s RLG’s trajectory took a sharp turn. Auditor-General reports and media investigations revealed chronic underperformance on its promises. For the 2010 laptop deal, RLG delivered only 90,448 units of the 103,181 ordered (a shortfall of 12,733 laptops worth ¢6.37 million). Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee later agreed RLG must refund ~¢6 million for undelivered machines. RLG’s own managers contended that missing laptops had manufacturing defects and were replaced under warranty, but the official finding was that RLG failed to fully honor the contract.

Similar gaps emerged in RLG’s youth-training programs. RLG had been contracted by Ghana’s youth and skills agencies to train thousands of unemployed youth in ICT and vocational skills. An Auditor-General report found RLG was paid ¢25.5 million to train 15,000 youth (plus another contract in smock-making and poultry rearing), yet it only reported training 4,222 individuals.

The Auditor-General ordered RLG to repay misused funds, citing poor oversight by the youth agency. Compounding these issues, RLG became entangled in political-financial scandals. One former board chair, who was also linked to RLG’s foundation, was implicated in diverting ¢75 million from the Savannah Accelerated Development Authority (SADA) toward RLG-affiliated companies. And in 2017 RLG’s CEO, Roland Agambire, was declared “wanted” by tax authorities for defaulting on ~GH¢14.3 million in corporate taxes, prompting the Ghana Revenue Authority to seal RLG’s Accra premises pending payment. Even the grand Hope City project, let’s just say, there was no hope for the city after all. After two years of launch, no construction had begun and the scheme was quietly abandoned.

By the late 2010s nearly all of RLG’s Ghana offices were shuttered. Its rise-and-fall prompted a deep soul-searching in Ghana’s tech space. RLG’s initial success, local assembling, brand-building and high-profile projects, had seemed to validate policies like “One Laptop per Child” and ICT-driven development. But its collapse prompted a probe into its underlying problems: the company overreached far beyond its core strengths, entangling itself with multiple government projects that it could not sustainably deliver. A source from Ghana’s tech community likened RLG to “Icarus” – a local champion that flew too close to the sun.

The RLG Impact and Lessons

RLG’s story is both cautionary and instructive for Ghana’s future tech enterprises. On one hand, RLG demonstrated that Ghanaian entrepreneurs could build indigenous brands and assemble devices locally – achievements which were not the typical Ghanaian’s wish list. On the other, RLG’s controversies eroded public trust. Its partial delivery on the school-laptop program and irregularities in youth training undermined confidence in “Made-in-Ghana” technology and raised questions about corporate governance. The RLG saga shows that true tech-sector development requires realistic scale and accountability, not just ambition or headline-grabbing contracts. For Ghana’s policymakers and entrepreneurs, key takeaways include:

Focus and Capacity

Avoid spreading resources too thin. RLG’s pivot from phones to laptops to building a $10B tech city suggests it is overextended. Future firms should align projects with core manufacturing capacities.

Transparent Partnerships

Public–private collaborations must have clear oversight. The Auditor-General’s auditing of RLG contracts led to refunds and sanctions; rigorous monitoring from the outset can prevent costly failures.

Local Value-Addition

Critics noted that around 90% of RLG’s hardware components were imported from Asia. Genuine “local manufacturing” should strive to develop upstream capability, not merely final assembly.

Governance and Ethics

RLG’s entanglements (e.g. SADA links) underscore the need for clean corporate governance. Ghanaian tech firms must build trust through probity to sustain support.

Sustainable Growth

The rush for awards and expansion must be balanced by sustainable business models. RLG’s rapid growth raised expectations that could not be met during downturns.

RLG’s legacy is mixed: it inspired a generation with a vision of Ghanaian-made gadgets, but its collapse serves as a reminder that lofty promises must be grounded in diligent execution and ethical management. Ghana’s tech sector continues to mourn the lost jobs and products of the RLG era, even as it takes valuable lessons from its fall.

Zepto Limited: Assembling Local Tech Ambitions, One Device at a Time

Launched in 2010, Zepto Limited took up the mantle of local assembly after RLG’s rise. A joint Danish–Ghanaian electronics company, Zepto relocated its manufacturing plant from Denmark to Accra, pledging to make “up-to-the-minute” laptops and HD TVs in Ghana. It branded itself as Ghana’s first high-tech assembly plant, aligning with national ICT policies like the digitization of television. Zepto’s early output was modest but symbolic: in 2012 it announced having delivered over 700 laptops to Ghanaian school teachers on easy-payment plans, under a program meant to improve learning with ICT. These machines, emblazoned with the Zepto logo, signaled that Ghana had another indigenous tech maker on the scene.

Zepto’s public profile grew through strategic partnerships. In 2016 it teamed up with Microsoft to launch the Zepto UmiTab 10.1, a Windows 10 tablet with a detachable keyboard, in Ghana. At the launch, CEO Charles Ofori emphasized affordability and after-sales support: the UmiTab sold for GH¢999 (roughly USD $200) including a 1-year Microsoft Office subscription, and came with a one-year warranty. The company even committed to donating tablets to youth-training initiatives (10 units to the British Council’s Skills Hub) as part of a broader education drive.

Zepto also reportedly introduced plans to finance purchases for students and large orders by institutions, aiming to leverage Ghana’s “one laptop per child” style policies to boost local consumption. In an interview the CEO noted that Ghana’s heavy taxes on electronics kept prices high, and welcomed recent tax cuts on devices to help Zepto bring costs down. Unlike RLG at its peak, Zepto did not aggressively court government contracts beyond these initiatives, and instead focused on niche markets (education, public service) and own-branded products.

On performance vs. expectations, Zepto’s results have been mixed. It succeeded in establishing Ghana’s second electronic assembly plant (after Omatek), and in maintaining operations for several years, a notable achievement given the difficulty of local manufacturing. Its partnership with Microsoft and donor-funded projects showed international and NGO confidence in its mission. However, Zepto’s scale remained small relative to national needs. The 700 laptops it sold over two years to teachers was a fraction of the thousands needed for all schools, and its tablet sales did not fundamentally shift the market.

While RLG became synonymous with “Made in Ghana” devices, Zepto’s name remained relatively obscure to most Ghanaians. Meanwhile, a flood of cheaper imports still dominates the consumer market, a 2015 e-waste study noted that new equipment was only 30–40% of Ghana’s electronics, and identified Zepto (with Omatek and another firm) as one of the few local assemblers in a sector overwhelmed by second-hand imports. In other words, Zepto has made Ghana’s industrial dreams tangible on a small scale, but the broader impact on domestic availability of devices is still limited.

Zepto has largely avoided the scandals that marred RLG. There is no public record of Zepto failing to deliver government laptops or dodging taxes. Its reported ethics and transparency remain good: for example, its collaborations and donations were publicized through Ghanaian and even Microsoft press releases. If anything, critics might point out that Zepto’s products rely heavily on foreign parts (like virtually all electronics in Ghana) and thus do not yet build a complete local value chain. Still, its role in the ecosystem is significant: Zepto demonstrates that an African country can host electronics assembly with some local leadership. It also spurred skills development – Zepto’s CEO even talked of offering vocational training in hardware and software, echoing RLG’s original ethos but on a smaller scale.

Lessons: The Zepto experience underlines a few themes for Ghana’s indigenous tech firms:

- Sustainable Niche Focus: Zepto targeted education and government-aligned projects rather than attempting an all-out consumer assault. This narrower focus can be a more sustainable entry strategy for local producers.

- Strategic Partnerships: Teaming up with a global tech brand (Microsoft) lent Zepto credibility and ensured software integrity. Future Ghanaian startups should seek such alliances to gain customer trust and market access.

- Government and Policy Support: Zepto benefited from educational programs and modest tax incentives. Consistent government support (e.g. keeping device taxes low, integrating local manufacturers into public ICT schemes) can nurture indigenous firms, but such support must be carefully managed to avoid the pitfalls seen with RLG.

- Scalability Challenges: As the e-waste report noted, Ghana’s device needs far exceed what small assemblers can provide. Building up to produce hundreds of thousands of units will require infrastructure, investor backing and deeper technical capacity. This remains a gap for Zepto-like ventures.

- Long-term Viability: Zepto shows longevity relative to RLG, but it remains unclear if it can achieve profitability or growth beyond pilot projects. It is a sign that an “assembling ecosystem” can exist, but the next step is scaling through market penetration or export.

Zepto’s journey is not one of spectacular failure but rather of cautious progress. It underscores that, even with good intentions and some achievements, Ghanaian tech manufacturers face systemic headwinds: a relatively small domestic market, stiff competition from imports, and the constant need for external capital and technology. Unlike RLG’s meteoric rise and crash, Zepto’s path has been steadier but slower. Both stories converge on one point: Ghana can nurture indigenous tech firms, but success requires grounded expectations, solid execution and a supportive ecosystem. As Ghana moves forward with new digital initiatives, the experiences of RLG and Zepto will inform policymakers and entrepreneurs alike about what it really takes to build technology “made in Ghana.”

Subscribe to MDBrief

Clean insights, a bit of sarcasm, and zero boring headlines.